This was originally posted on my other, personal blog The Lyons Din.

His parents named him Martin Behrman French, in honor of the one-time mayor of New Orleans who counted his father, former Louisiana State Representative Henry David French, as one of his dear friends. Oddly, his family would forgo the simpler, more usual name of Martin, calling him Behrman (pronounced Ber - man) instead.

His wife called him Behrman too, but with a distinct west bank of New Orleans roil that turned it into "Boy-man." Only a handful of people ever called him Martin and he was never, ever a Marty.

I just called him Grandpa.

Behrman grew up in Algiers on the west bank of New Orleans, in a traditional camelback shotgun double at 813 Pacific Avenue. His mom was a big fan of ginger beer (a precursor to ginger ale) back in the day, and used the ceramic tan bottles to line the garden. There were hundreds.

When he was about 6 years old, he was playing with friends in his neighborhood when one of them, carrying a BB gun, tripped. The weapon fired and hit Behrman in his left eye, permanently blinding him on one side.

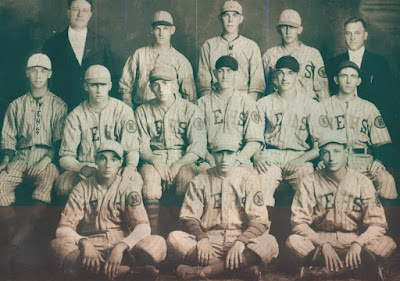

But that didn't stop Behrman from playing football or baseball. He matriculated at Warren Easton High School in New Orleans, every day riding the ferry across the Mississippi River, then taking a streetcar down Canal Street. Behrman was a member of the Eagles baseball team and later played on a few of the semipro teams in and around New Orleans. He loved to boast that he played with the great Mel Ott.

Martin Behrman French, back row, third player.

In 1926 Behrman married a girl who lived in the neighborhood, Evelyn Himel Cross, who had broken up with the Mothe boy because she didn't want to marry the undertaker's son. (The Mothes later opened one of the largest funeral homes in the city.)

Around that time, Behrman went to work for Bell Telephone Company. His first job was in an office, but when he got laid off, he offered to go to work as a pole digger. He did that for several years until he was able to work his way back to a desk and a position as office manager. His job took him from New Orleans to Patterson, where his only child, Lettie Lee, was born, to Baton Rouge and, finally, to Houma. He would retire in 1969 after 45 years with the company. The Houma Courier did a story on his retirement.

To this day I can't help but think of Edith and Archie Bunker when I think of my grandparents. He was a cantankerous old coot for much of my lifetime, a "get off my lawn" kind of guy who nearly had a stroke anytime anyone of the male persuasion dared to pull into our driveway to visit me. She was the sweetest soul you'd ever meet, who put up with his ire and anger for more than 60 years. Somehow, they made it work.

Grandpa loved to fish, too. But just a few days after his boss retired, Grandpa took him out on his boat fishing. The man suffered a heart attack and died on the trip and, shortly thereafter, Grandpa put his boat up for sale.

But he also doted on us grandkids, teaching my brother, Rhett, the proper way to throw a baseball and trying to turn my nephew, Lee, into a mini-Archie Manning back in the day. I wasn't into the sports thing, but we did share a love of music.

Paw Paw may have spent 45 years working for the telephone company, but in his heart, he was an entertainer. I don't know when he first picked up an instrument, or how, but I know he loved music -- playing it, writing it, performing it. He played the guitar, the banjo, the ukulele and the organ.

But the banjo was his jam. And I'm guessing, if he had a say in the matter, he would have preferred to be called "Mr. Banjo." It was the title of one of the many tunes he played.

Most of my early childhood memories of my grandfather are of him with a banjo across his lap. He played it often on the breezeway of his home in Houma and he had frequent jam sessions with his musical pals, Gene Dusenberry and Sonny Thibodeaux. (And one of my greatest regrets is that I never asked Mr. Sonny to teach me how to play the Hawaiian/slide guitar.)

He also played at the annual Telephone Pioneers picnics, before downtown Mardi Gras parades and at any other public event that called for musical entertainment. But Grandpa and Grannie were most known for their frequent gigs at the local nursing homes in Houma where they -- great-grandparents, mind you -- would perform for the "old folks."

|

| Behrman and Evelyn French, performing at one of the long term care facilities in Houma. |

The two of them had compiled a large repertoire of really silly songs from the early 19th Century, including such novelty tunes "Once There was a Little Pig" (in which the baby pig died and the mother pig cried herself to death), "The Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia," (in which a cow was loitering on a railroad track and got run over), and "The Burglar Beau," about a burglar who happened to choose the home of a one-eyed, toothless woman for his victim. And we all learned to spell Mis - sis - sippi by singing it every time we crossed a bridge.

But Gramps also wrote a few ditties himself. When his adopted home of Houma in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana celebrated its sesquicentennial in 1972, Grampa wrote a lovely song called "This is the Place."

This is the place I'll carry on.

This is the place I toot my horn.

Houma in Terrebonne."